Get Shorty

My first job out of college was as a trader for a trust company, in a department called automated cash management. That meant I traded sweep accounts and put money into, or took it out of, money market funds on behalf of our clients. There was no strategy involved, the system told me how much needed to be traded, and I made a phone call to execute the movement of cash. Money market funds trade at $1/share (except for a couple times when a couple funds broke the buck ) and it was all very straightforward. I started on Dec 27, 2004 when money market funds were yielding just above 2%. The fed funds rate had been on a steady grind higher and was just raised to 2.25%. At the time, money market funds were thought of as nothing more than a default investment. A holding place for short-term periods while investors thought about what to do next. But then things changed. By the end of 2004, money market yields were at 4% and the fed funds rate had been raised another 200 basis points — on its way to a terminal rate of 5.25% in March 2007. The 6-month Treasury yield rose almost 200 basis points over the same period, to peak out at 5.3% right around the last Fed rate hike of the cycle. Sound familiar? There were many differences between that cycle and this one, but we have to admit there are some eerie similarities to today. And we all know the end to that cycle was anything but soft.Follow the Flows

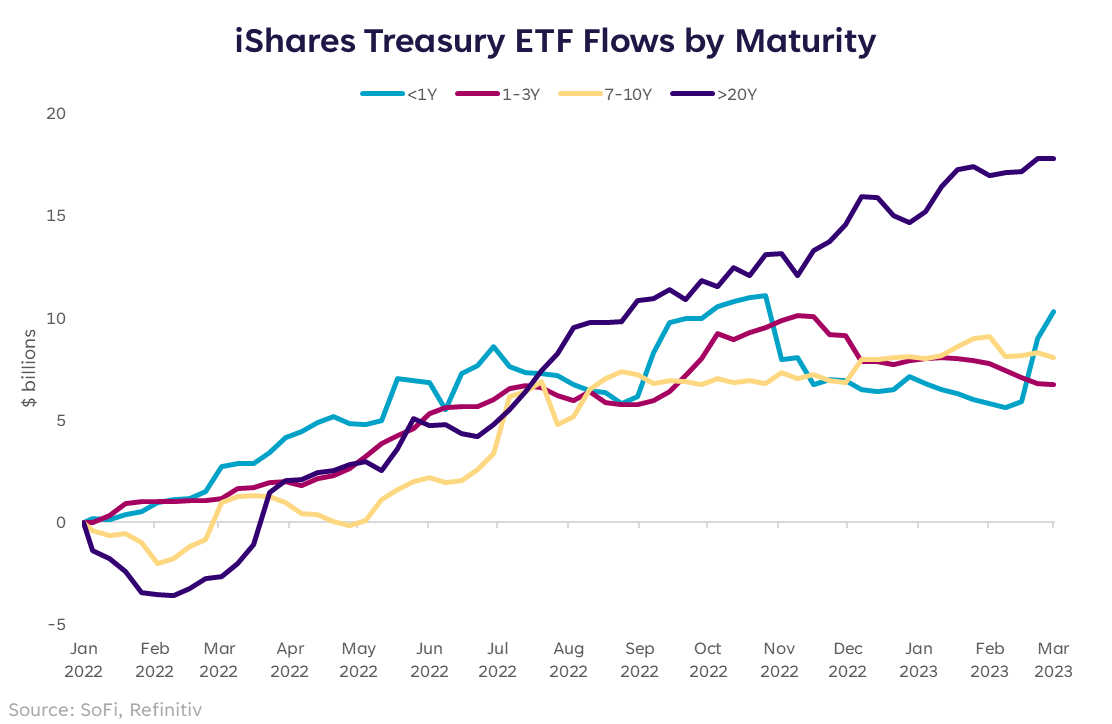

Rather than get too deep in the comparison weeds of economic data, let’s focus on the fact that boring money market funds and short-term “cash” instruments are back in style. So much so that if we had fashion magazines for asset classes, money markets would be on the cover of Vogue and Anna Wintour would be pushing dresses made of $1 bills. Although all of the government bond ETFs represented below have seen a steady grind higher in cumulative flows, the recent spike in flows for maturities of less than 1-year is notable. Some may look at this and say it’s a crowded trade, which is usually not a good sign for future return prospects. But when we’re talking about securities that are bought and sold more for their yield than their price, that concept doesn’t hold as much weight. After so many years of yield-starved markets, investors have piled into short maturity instruments because the yield is the gift that keeps on giving. Oftentimes, investors pile into cash and short-term securities because they’re wary of the future. That’s likely true now. But the other force at play is that people are betting on the looming end of this cycle, which typically brings a drop in policy rates, thus a drop in short-term yields (and subsequent rise in short-term government bond prices). If that bet is correct, this would be a pretty good trade…even at crowded levels. Not to mention, if short-term yields fall, the yield curve inversion would go away, reducing the risk of recession, right??I Never Liked Dominos

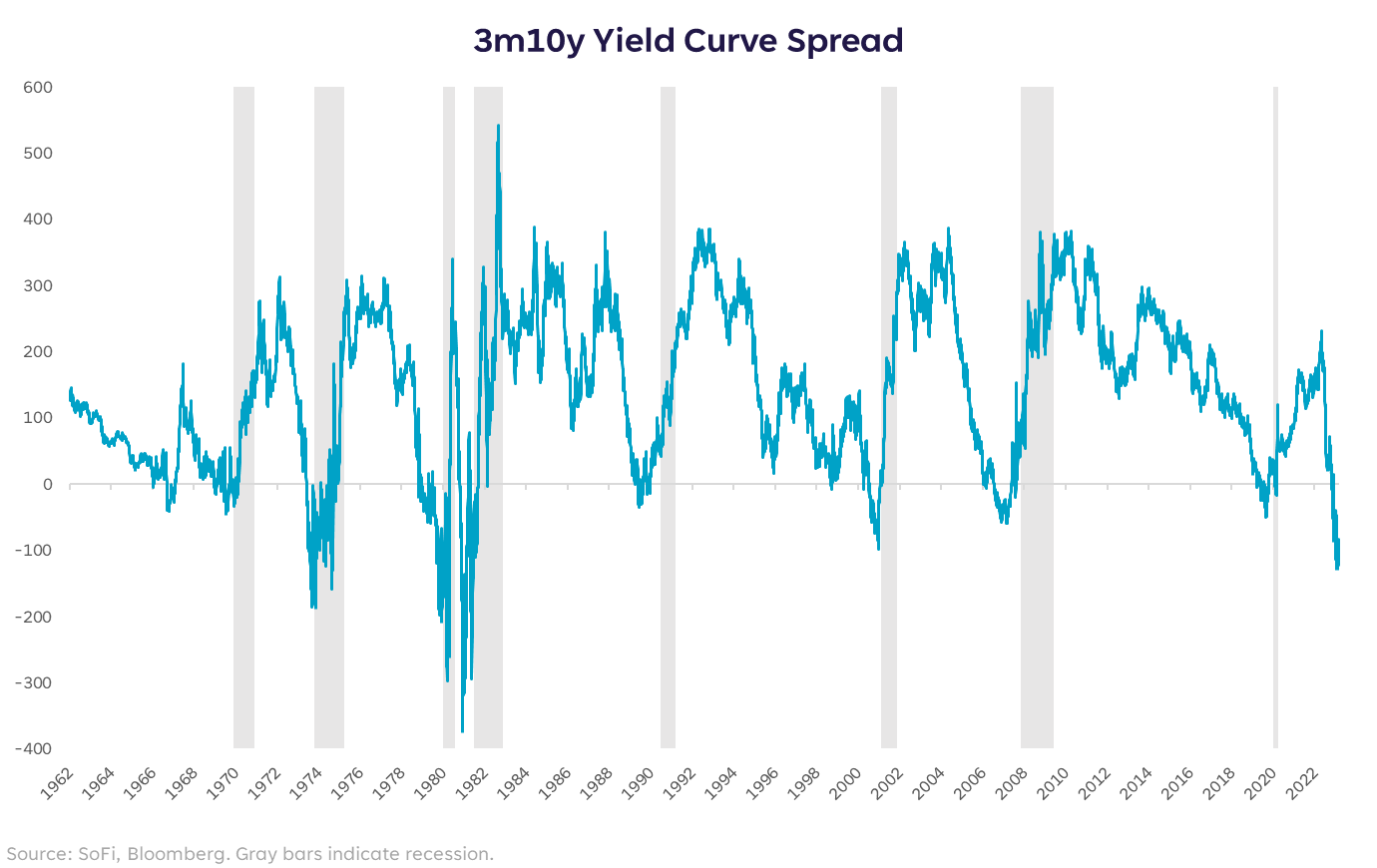

I always preferred the game of checkers — and the pies from Pizza Hut — over dominos, in both cases. But my point here is that this all has a domino effect, and if the effect I’m about to outline ensues (nothing is guaranteed), the optimists won’t like these dominos either. Yield curve inversions happen for a reason. The Fed raises rates and brings up the short-end, while people get scared and buy the long-end. Soon enough, the teeter totter flips and we’re upside down. The current inversion between the 2-year and 10-year Treasury yields is almost 90 basis points. An even more specific inversion to watch is that between the 3-month and 10-year Treasurys. This represents the shortest of short maturities and perhaps best portrays what the Fed is doing. The good news is investors can get the highest yield since 2007 on 3-month Treasury Bills. The bad news is this inversion is the deepest it's been since the early 80s. Inversions on this measure have preceded recessions every time but once since 1962. And even when an inversion occurred in 1966 without a recession to immediately follow, it was during a time when inflation was a problem that didn’t get solved, only to rear its ugly head and cause a deep recession a few years later. Again, sound familiar? That’s exactly what the Fed is trying to avoid. Here’s the domino effect: if the Fed pivots (i.e., cuts rates), short-term yields would fall quickly. With inflation at these levels, the only reason the Fed would pivot before inflation nears its target is because economic data worsens and worries them. The yield curve would flatten or un-invert, but only because things got worse, not better. If things got worse, corporate earnings are likely to follow suit and equity prices would feel the pressure. That produces the trifecta of recession: market drawdown + earnings contraction + economic pain. This is why we have to be careful what we wish for. I don’t wish for a Fed pivot anytime soon because of what would have to happen to convince them to do so. But with each passing week of high yields on the short-end of the curve, the question of when and why those yields come back down gets louder and louder. Some have said yield curve inversions don’t matter this time because things were manipulated by monetary policy. But isn’t monetary policy the thing that causes yield curve inversions every time? I don’t think it’s that different this time.

Please understand that this information provided is general in nature and shouldn’t be construed as a recommendation or solicitation of any products offered by SoFi’s affiliates and subsidiaries. In addition, this information is by no means meant to provide investment or financial advice, nor is it intended to serve as the basis for any investment decision or recommendation to buy or sell any asset. Keep in mind that investing involves risk, and past performance of an asset never guarantees future results or returns. It’s important for investors to consider their specific financial needs, goals, and risk profile before making an investment decision. The information and analysis provided through hyperlinks to third party websites, while believed to be accurate, cannot be guaranteed by SoFi. These links are provided for informational purposes and should not be viewed as an endorsement. No brands or products mentioned are affiliated with SoFi, nor do they endorse or sponsor this content. Communication of SoFi Wealth LLC an SEC Registered Investment Advisor SoFi isn't recommending and is not affiliated with the brands or companies displayed. Brands displayed neither endorse or sponsor this article. Third party trademarks and service marks referenced are property of their respective owners. Communication of SoFi Wealth LLC an SEC Registered Investment Adviser. Information about SoFi Wealth’s advisory operations, services, and fees is set forth in SoFi Wealth’s current Form ADV Part 2 (Brochure), a copy of which is available upon request and at www.adviserinfo.sec.gov. Liz Young Thomas is a Registered Representative of SoFi Securities and Investment Advisor Representative of SoFi Wealth. Her ADV 2B is available at www.sofi.com/legal/adv. SOSS23030203